“Diversify your risk in fantasy football, just like you would a stock portfolio”

This is terrible advice in fantasy football, especially in tournaments.

This article will focus on both the theory and math behind stacking, helping you understand why it’s essential to increasing your odds of winning a hefty chunk of cash at season’s end. To those skeptical regarding stacking and its benefits, by the end of this article, you won’t be.

The really fun part (in my completely unbiased opinion) is the final, large section of this article, where I dive in-depth with data from Underdog Fantasy’s Best Ball Mania tournament from 2020. I break down how often QB-WR duos entered actual tournament lineups from last year. Then I analyze the rates that teams advanced throughout the tournament based on the different stack combinations they did/didn’t roster. Spoiler alert: the data greatly favors stacking.

30-Second Primer on Best Ball

Unlike traditional redraft leagues where you set your lineup during the season, in best ball, you focus on the best part of fantasy football: drafting. On Underdog Fantasy, you draft QB/RB/WR/TE over 18 rounds, and then during the season, your highest scoring players make your lineup.

You might finish a draft with two QBs, five RBs, nine WRs, and two TEs. Each week in-season, the highest scoring QB, two highest scoring RBs, three highest scoring WRs, and highest scoring TE make your lineup, as well as the next highest scoring player that’s not a QB to fill your flex spot. Rather than setting a lineup and crossing your fingers that you started the right guy in your flex spot, Underdog automatically puts the highest scoring players into your starting lineup when that week’s games are over.

At the end of the fantasy football season, whichever team has the most cumulative points wins the league.

Start best ball drafting to spend less of your time scanning the waiver wire or driving yourself crazy deciding which field-stretching receiver should go in your flex this week, praying he gets a touchdown. Promo code UNDERWORLD when you sign up for Underdog Fantasy gets you $25 extra when you deposit $25 (as well as helping to keep me employed and away from a corporate analytics career I’m sure I would hate).

Stacking in Theory

Before diving into the math behind why you should be stacking using detailed data from last year’s Underdog Fantasy Best Ball Mania tournament, we will first think about this puzzle theoretically. If you’ve played fantasy football before, you know how frustratingly random touchdowns can be.

Another difficult variable we contend with every week is which teams will be high-scoring. While the Chiefs and Bills will put up three or more touchdowns every Sunday, even a high-octane offense like the Chargers, with Justin Herbert at the helm, was wildly annoying to predict. The Chargers had seven straight games with three or more touchdowns before scoring 17 points against Buffalo and then getting shut out against New England the following week.

Football is a grueling sport to predict, and this is where stacking enters the fold. Stacking allows us to limit how many different variables we have to get correct each week. If that last sentence went over your head, the below example with real NFL players will illustrate this concept of how many “different variables” we must get “correct” in a given week.

We’ll stick with Herbert because I’m a displaced San Diego Chargers fan. Herbert currently goes in the seventh round on Underdog, and his WR1, Keenan Allen, is typically drafted in round three. Another wide receiver with a similar ADP to Allen is Michael Thomas.

The two potential player combinations are Allen round three followed by Herbert in round seven, or Thomas round three with Herbert round seven.

Fast-forward to week one, and Herbert has a great game, throwing for 325 yards and three touchdowns. It’s incredibly unlikely Allen puts up two catches for 37 yards in this game, since he’s Herbert’s most trusted receiver. There’s a decent chance one of those touchdowns, and many of those yards, go Allen’s way. We had one big event go in our favor: the Chargers having a great day on offense. Yet two of our players are now entering our best ball lineup for that week.

What if we had taken Thomas instead of Herbert? For both of them to enter our best ball lineup for this week, we still need the Saints to have a productive day offensively for Thomas to most likely pay off. By not stacking Herbert and Allen, we now need two different variables to go our way: the Chargers and the Saints having strong offensive showings.

In the sport of football, where so many variables are outside our control, it’s nice to only need to root for one team’s offense to succeed to ensure that two players enter our best ball lineup with spike weeks; had we not stacked, we would need to root for two teams’ offenses to succeed to ensure that two players spike in our best ball lineup.

The Basic Math

We can zoom in on a single play in this game, where Justin Herbert throws a 25-yard touchdown pass. Using Underdog scoring, a quarterback gets one fantasy point every 25 yards passing, and four points per passing touchdown. A 25-yard touchdown pass nets Herbert five total fantasy points. It’s not a given, but there’s a decent chance this touchdown was thrown to Keenan Allen (30-percent of Herbert’s touchdown passes in games they overlapped went to Allen in 2020). If it goes to Allen, he would get a fantasy point every ten receiving yards, half a point for the reception, and six points for a receiving touchdown, for a total of 9.0 fantasy points on that passing play.

If we had stacked Herbert and Allen, that single pass play gets us 14 fantasy points. Of course it’s likely (~70-percent in 2020) Herbert throws this touchdown to another receiver on the Chargers, but there’s absolutely zero chance this touchdown is thrown to Michael Thomas. If we had rostered Thomas with Herbert, then we would get five fantasy points no matter what on this play, with no chance of hitting 14 (9 for Allen, 5 for Herbert) fantasy points.

Another way to think about this comparison is that a Herbert 25-yard touchdown pass’ expected fantasy points if you have Allen is 5 + (.3*9) = 7.7 expected fantasy points. That equation factors in a 30-percent chance that Allen gets 9 fantasy points from that play, since he caught 30-percent of Herbert’s touchdowns in games he was active last year. If you have Thomas, not Allen, your expected fantasy points when Herbert throws a 25-yard touchdown pass is 5 + (0*8.5) = 5 expected fantasy points because there is a 0-percent chance Thomas catches touchdowns from a non-Saints quarterback.

“Josh, you took Keenan Allen in round three, shouldn’t you diversify your risk and take a different quarterback?”

You took Allen in round three as a top-10 wide receiver. You have officially planted your flag on him having an excellent season. Yet, you’re worried Herbert won’t have a good season, so you take Allen but then grab a non-Herbert quarterback instead. You are now threading the needle, setting up a universe where Allen is having a monster season, yet his own quarterback is struggling. If you don’t think the whole Chargers offense will cook, why take a player from that team in round three? Remember, we are trying to win this tournament, not get fourth place in our opening 12-person draft, and you need all your early round picks to fire for that to happen.

The next time your ignorant friend at the bar questions the validity of stacking in best ball, you can provide them with this explanation. Expect your friend to buy you a beer afterwards, as he/she will also have seen the light.

Stacking and Correlation

When discussing stacking, you’ll often hear that fancy term “correlation” floated around. But what does it mean in very simple terms?

Think of correlation in fantasy football as two players’ fantasy points moving in similar or opposite directions. If they move in similar directions, that’s known as positive correlation; if they move in opposite directions, negative correlation.

Patrick Mahomes and Tyreek Hill are very positively correlated. If Mahomes has a lot of fantasy points one week, there’s a good chance Hill does too, and vice versa.

Baker Mayfield and Nick Chubb are not as closely correlated as Mahomes-Hill, and some years they may even be negatively correlated. If Baker has a lot of fantasy points in a week, there’s a strong chance the Browns are scoring through the air and Chubb is not utilized frequently in the passing game. Conversely, if Chubb has a big game, he’s most likely scoring his touchdowns on the ground, taking away from Baker’s fantasy points total that week. While there is no chance for Mahomes and Hill to be negatively correlated, a QB-RB duo like Baker-Chubb is more likely to have the players alternate strong fantasy performances, rather than hit their ceiling on the same week.

I used the approximately 40,000 entrants in Underdog Fantasy’s 2020 Best Ball Mania tournament to generate ADP data for each player, and then assigned QB1, RB1, RB2, WR1, WR2, WR3, WR4, TE1, TE2 to each team. For example, the 2020 Buffalo Bills had Josh Allen as the clear QB1 based on ADP (91.8). The RB1 was Devin Singletary (69.5 ADP), RB2 was Zack Moss (91.2), WR1 was Stefon Diggs (63.1), WR2 was John Brown (104.8), and the WR3 was Cole Beasley (198.9).

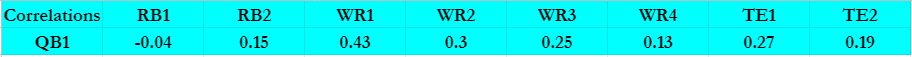

I then analyzed the correlations between the QB1 in an offense and the RB1, RB2, WR1, WR2, WR3, WR4, TE1, and TE2 of that respective offense. These numbers below were averaged among all 32 NFL teams.

The only negative correlation present was between the QB1 and the RB1 at -0.04. This makes intuitive sense; quarterbacks score many of their fantasy points through passing touchdowns, while running backs score a large portion through rushing touchdowns. Passing and rushing touchdowns are at odds with each other. Remember though that this is an average of all 32 teams. Looking ahead to 2021, I expect this negative correlation to hold. Though there are several teams that I would expect to have positive correlation between the QB and RB. One quick example is the Arizona Cardinals, since Chase Edmonds has historically scored a large percentage of his touchdowns through the air.

The QB1 and RB2 in an offense are positively correlated, with an average value of 0.15. Many secondary RBs on teams are a pass-catcher like Nyheim Hines or James White, so this does make some intuitive sense.

The QB1 correlation with their WR1, WR2, WR3, and WR4 is 0.43, 0.30, 0.25, and 0.13, respectively. We could say that, statistically, a WR1 in an offense is just over three times more correlated to their QB than a WR4 in an offense is, since 0.43 is greater than 0.13 multiplied by three.

The QB1’s correlation with the TE1 and TE2 in an offense is 0.27 and 0.19, respectively. The TE1 in an offense is just in between the WR2 (0.30) and WR3 (0.25) in an offense regarding positive correlation. While tight ends don’t catch many passes nor rack up much in the receiving yardage department, a higher percentage of their catches are touchdowns, which do score fantasy points. Those touchdowns through the air help tight ends correlate well to their quarterback.

Best Ball Tournament Stacking Results (2020)

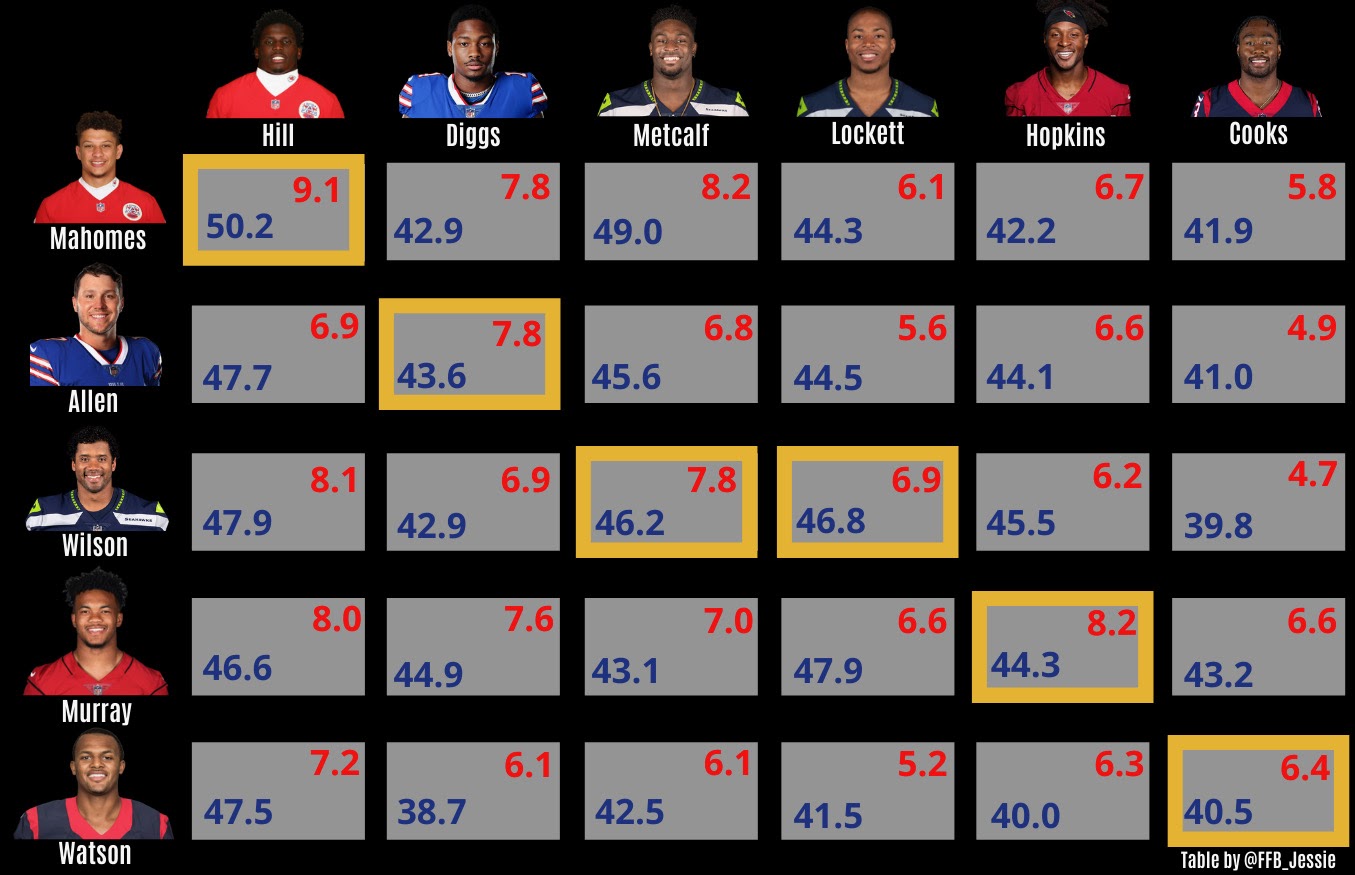

Before analyzing anything too complex, like team win rates based on the types of stacks present on that team, we can study individual QB-WR combinations to reinforce the concept of correlation by seeing stacks in action.

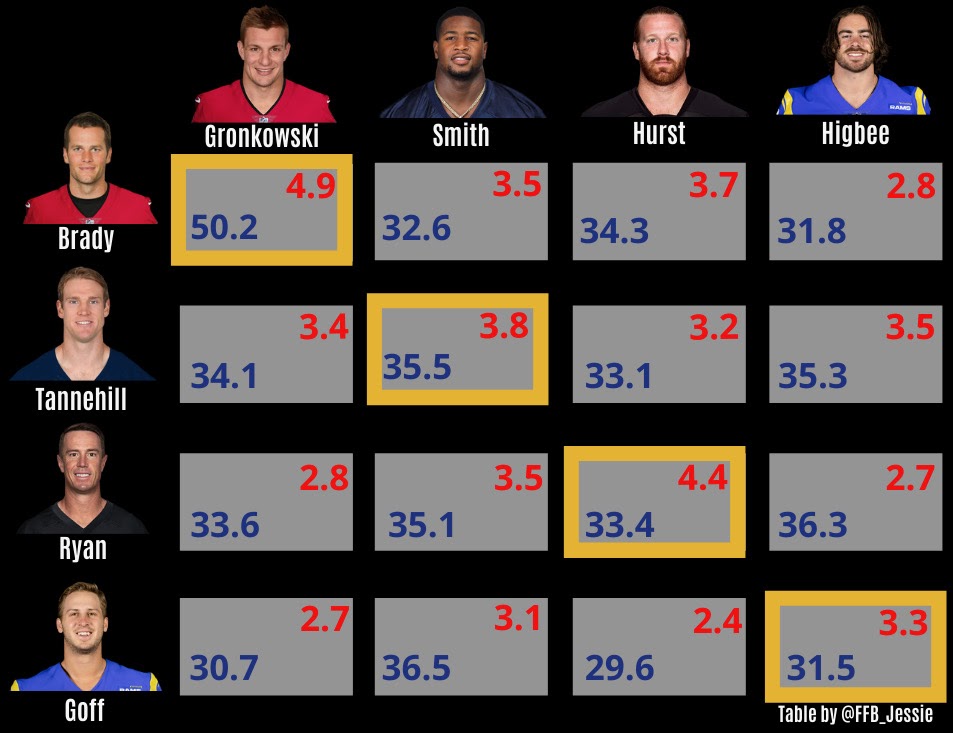

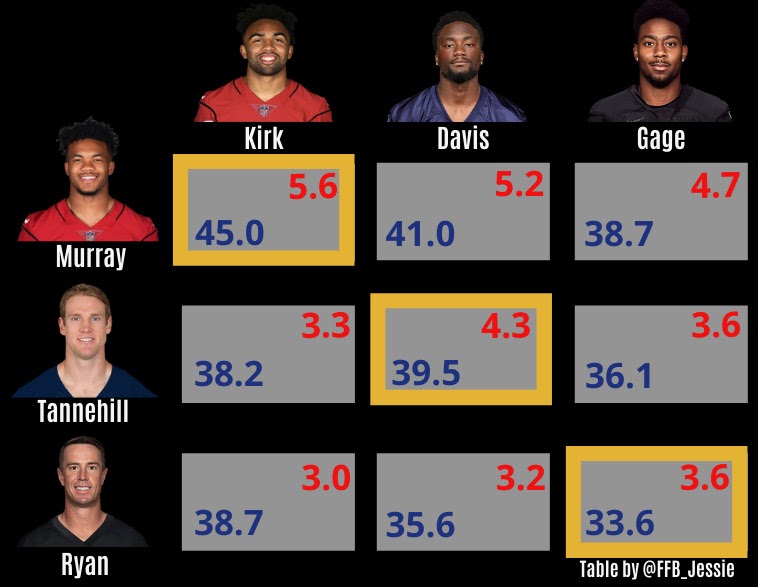

The table and descriptive key below outline popular stacks from 2020, using data from the Underdog Best Ball Mania tournament.

The way to interpret this table is as follows: the red number top right is the average number of times that the QB-WR duo entered peoples’ best ball lineups from weeks one through 13 of the 2020 NFL season (round one of this tournament was cumulative points from the first 13 weeks of the season), and the blue number in each box is the average fantasy points scored by both players during the weeks that both entered your lineup. All these QB-WR combinations appeared in at least 100 different tournament teams to ensure adequate sample sizes were reached.

As an example, among teams that drafted both Patrick Mahomes and Tyreek Hill, both players entered best ball lineups in 9.1 of the 13 weeks on average, scoring 50.2 combined fantasy points when they did. On the other hand, teams that drafted both Mahomes and DeAndre Hopkins had that pair enter their best ball lineups together only 6.7 of the 13 weeks on average, for only 42.2 fantasy points combined per week.

The major takeaway from this table should be the importance of stacking for gaining correlated spike weeks from both your QB and WR.

Note that for these QB-WR pairings, the teammates usually score more fantasy points together than the non-teammates. In nearly all the pairings, the players enter your lineup more often together (red number) when on the same team. Best ball teams need points to be scored each week. And you have a very limited number of players on your roster; having a correlated portion of your team ensures that players enter your optimal lineup on the same week to lessen the chance that your team ever has to take five or fewer points at a starting WR slot any given week.

Tight ends are also correlated to their quarterbacks, as mentioned in the prior section. The below table illustrates this phenomenon. The red number is greatest in all four situations when the QB and TE are on the same team.

Of course stacking extends to ancillary wide receivers, too. And the below chart notes a few pairings of quarterbacks with their second or third option in the passing game. While these examples have been picked to demonstrate the upside of stacking, there is no guarantee that your QB-WR2 combination will crush in best ball any given year; rather it’s knowing the upside that drafting the “correct” QB-WR2 combination can help you win your best ball league. Ryan Tannehill–Corey Davis and Matt Ryan–Russell Gage were two stacks in particular that required no heavy investment in draft capital, yet both paid off big time for their drafters.

I believe these stacking tables to be one of the real highlights of this article, and they are courtesy of Jessie Dombrowksi, our content intern for this summer.

Don’t Reach on Stacks

Many in the fantasy football community are aware of the power of stacking. But a lesser discussed aspect of stacking is the patience and willpower needed to avoid “reaching” to get your stacks. Reaching on a stack is when you take the QB-WR or QB-TE or QB-WR1-WR2 from the same team well ahead of their ADP to make sure that you and only you are able to get those players in your draft.

In the next section, I’ll lay out several stacking combinations that real fantasy gamers used in the 2020 Best Ball Mania tournament on Underdog, separating win rates for these stack combinations based on whether or not the drafter “reached” for that stack. But initially, we should make sure the theory behind not reaching is understood. And an example with real players using real 2021 player ADPs on Underdog is the best way to accomplish this.

Right now, D.K. Metcalf gets drafted in the late second round on Underdog, and Russell Wilson gets taken late round six or early round seven. If you were anxious about getting those two players, and you really really wanted to make sure that you had the boys from Seattle on your team, you could take Metcalf in the first round, and Wilson in the fifth round, practically guaranteeing that you have the Seahawks stack on your best ball roster. Just to complete this thought experiment, say that you took Najee Harris in round two and Michael Gallup in the seventh round.

If the Seahawks are one of the best offenses in all of football in 2021, you have a good chance to be one of the top two teams in your opening division in the tournament.

For reference, the top two highest scoring teams from each initial 12-person draft go on to the second round of the tournament, and that second round begins in Week 15 for the 2021 season. Let’s say that the Seahawks stack takes you to a second place finish via total points from the first 14 weeks of the 2021 season. You would then move on to the second round of the best ball tournament, where you are randomly assigned to a group of 12 teams, where the 11 others also finished first or second in their opening 12-person draft through 14 weeks.

Suddenly, you are now facing other teams with Wilson and Metcalf. After all, if those two helped you advance in the tournament, they probably helped many other teams, too. To reiterate, in this reaching thought experiment, you took Metcalf (round one), Harris (round two), Wilson (round five), and Gallup (round seven). In the next round, you will be facing someone who didn’t reach for their stacks.

In round two of the tournament, your team is a sinking ship when you face someone who took Dalvin Cook round one, Metcalf round two, Tee Higgins round five, and Wilson round seven. Unfortunately, your team is not likely to score more points when it’s just an objectively worse roster on paper.

Dalvin Cook is better than Najee Harris, and Tee Higgins is better than Michael Gallup.

In best ball tournaments, the payout structure incentivizes getting into the later rounds of the tournament. Advancing out of round one of the tournament nets you only slightly more cash than your entry fee. I understand it’s difficult to resist reaching on stacks. But I assure you that letting the players fall to you is more profitable in the long run.

Here’s another thought experiment: you drafted D.K. Metcalf in round two and Tyler Lockett in round four. Who are you competing with for Russell Wilson? No team is incentivized to reach and take Wilson ahead of ADP since there’s no stack available to anyone else. You have strong odds of Wilson falling to you. And there’s no need to take him well ahead of his ADP.

If this whole section seemed obvious to you, you’re actually one step ahead of many big name “analysts” on Twitter. I’ve seen at least half a dozen well-known analysts gloating and victory lapping their stacks on Twitter. Even when they reached multiple rounds ahead of ADP to lock up a “sexy” stack.

Cold Hard Data on Stacks Paying Off

We return to Underdog Fantasy’s flagship tournament from 2020, Best Ball Mania. Using comprehensive data detailing each pick made by each of the 40,000 participants, I put together a stacking dataset. I was able to see every type of stack made by each drafter; as well as what pick number those players were taken at.

For this next section, I’ll be defining a reach as any time the combination of players is less than 90-percent of those two players’ total ADP. If you didn’t understand, and were intimidated by, that last sentence, a simple example will alleviate your anxiety.

Looking at all 40,000 drafts from last year’s Best Ball Mania tournament, DeAndre Hopkins was taken at pick No. 22 on average, and Kyler Murray was taken at pick No. 70.

22 + 70 = 92, and 90-percent of 92 is 83. To not be considered a reach, my 90-percent rule would dictate that the combined pick number of Hopkins and Murray be at least 83. So, if you grabbed Hopkins at the 2.06 (pick No. 18) and Murray at the 6.06 (pick No. 66), 18 + 66 = 84, which is larger than 83. Therefore, I would not consider this a reach on a stack.

To perform my stacking analysis, I averaged each player’s pick number from the roughly 40,000 drafts in Best Ball Mania. Then, team-by-team, I assigned each player to a place on the ADP depth chart. For example, Patrick Mahomes was the QB1 of KC in 2020, Tyreek Hill was the WR1, Travis Kelce was the TE1, Mecole Hardman was the WR2, Sammy Watkins was the WR3, etc.

As a reminder, in 2020, a team had to finish top two in their initial 12-person draft through the first 13 weeks to advance to round two of the tournament, a one in six chance, or 16.7-percent chance, of advancing.

To evaluate stacks, I looked at pairings of the QB with a WR and/or TE. I left RBs out of this analysis because it’s difficult to decipher which players were drafted specifically as stacking partners. And in general, starting RBs were negatively correlated with their QB.

Of all teams that had zero stacks anywhere, only 15.8-percent advanced to round two of the tournament; below the 16.7-percent baseline rate.

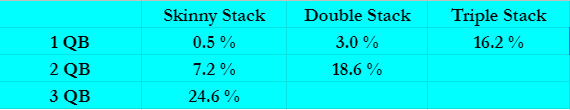

This table provides the percent increase above or below the “average” draft that these stack combinations achieved in 2020. I break down each of these numbers further below. The ones excluded were lacking proper sample size. And all these numbers are assuming no “reaches,” a concept also explained in-depth below. To interpret this, teams with two double stacks advanced in Best Ball Mania 18.6-percent more often than the average team.

Looking at the nearly 7,000 teams with one “skinny stack” (QB-WR or QB-TE), 16.8-percent of teams that didn’t reach on the stack advanced, right around the 16.7-percent baseline rate.

This could be a team where they had Mahomes and Kirk Cousins as their two QBs, with Adam Thielen as the only stacked WR. That team would qualify as only one skinny stack. Conversely, teams reaching beyond the 90-percent ADP threshold only advanced 11.9-percent of the time, well below the 16.7-percent base rate.

About 2,500 teams had one “double stack,” where one QB was drafted along with two of his WRs or TEs. These teams advanced 17.2-percent of the time to round two of the tournament when not reaching. 250 teams reached on one double stack, and only advanced 12.9-percent of the time, well below average. Another victory for those willing to be patient and not take their players two or three rounds earlier than ADP.

Roughly 600 teams had one “triple stack” on their team without reaching, a QB paired with three of his WRs/TEs. 19.4-percent of these teams advanced onto round two of the tournament, predictably higher than the 16.7-percent baseline. Those who loaded up three pass catchers with their quarterback well ahead of ADP only advanced five-percent of the time. Though it’s a small sample size of under 100 teams.

4,000 teams had two skinny stacks on their roster close to ADP. And 17.9-percent advanced in the tournament, while only 12.6-percent advanced when reaching on two skinny stacks.

Approximately 1,600 teams drafted two double stacks, two quarterbacks each with two of their own receivers, within 90-percent of ADP, and 19.8-percent advanced. Reaching round two of the tournament is a one in six chance initially. But by double stacking last year without reaching, you were able to trim that to a one in five chance. The power of stacking lies in needing to get fewer things right; double stack two quarterbacks, and if one of those two offenses has a good week, you already have two, if not three, players entering your best ball lineup. 365 teams reached on two double stacks, advancing only 16.4-percent of the time, slightly below the 16.7-percent baseline rate. While stacking helps, it’s not a panacea, and reaching for correlation is a negative expected value move.

The last combination I’ll highlight is teams with three skinny stacks. These 625 teams participated in round two of the tournament a whopping 20.8-percent of the time; the highest of any studied stacking combinations when the players totaled at least 90-percent of the cumulative stack ADP. 160 teams reached while triple skinny stacking, and only advanced 15-percent of the time. The second round of Best Ball Mania randomly assigned the advancing teams to new 12-person divisions for a one week playoff, with the winning team advancing on to round three.

When it’s a one week contest to determine first of 12 teams, DFS theory comes into play. And stacking is once again a useful -and necessary- tool to improve your odds against the field. Finishing first of 12 teams is a one in 12, or 8.3-percent chance, of success.

Of the 7,200 teams in this next round of the tournament, a touch over 1,500 had one skinny stack. These teams advanced to round three at an 8.4-percent clip, right around the 8.3-percent baseline.

570 teams had one double stack. They advanced to round three at a 7.9-percent rate, again slightly below the baseline.

There were only 150 teams with one triple stack. Their advancement rate was a paltry 5.9-percent, though it’s an incredibly small sample size.

We have hope when turning toward teams with two skinny stacks. Approximately 1,000 drafters in round two had teams with them, and 8.8-percent advanced, slightly above the 8.3-percent baseline.

Compounding the success of the dual double stacks, 10.9-percent of the 500 teams advanced from round two to round three. Likewise, teams with three skinny stacks advanced 10.7-percent of the time. Both these builds advanced at a roughly 20-percent clip out of round one, as well.

What Next

Stacking is not the only way to succeed in fantasy football, you can of course just pick the right players. However, player-centric analysis is difficult, comes with large error bars, and is extremely time-consuming.

The beauty of stacking is that you don’t even need to do much player research. You can just focus on stacking players from teams you expect to pass a lot. Yes, there is an additional edge if you are stacking and researching/projecting individual players, but fewer fantasy gamers have the time throughout the week to execute this part.

Bonus Question

I was asked a really interesting question on Twitter from @dynastymasters recently. He was curious if stacking in the Underdog best ball tournament could lead you to a “chalk” build. One where many others have a similar lineup, and you aren’t “unique” enough to actually win $1,000,000. I’m sure others have similar fears, allow me to assuage those.

When playing daily fantasy sports (DFS), you only take one QB. So a lot of people will have a similar lineup build from the start. For example, say the Chiefs and Bills are playing on Sunday. A really common trio in DFS lineups that week would be Patrick Mahomes–Tyreek Hill–Stefon Diggs to get a mini game stack going. In DFS, each player has a salary, and Mahomes/Hill/Diggs are all expensive. Naturally, if you start with those three, you’ll be saving money elsewhere in your lineup. And you may have a very similar set of complementary budget players to many others.

In a best ball tournament like Best Ball Mania II on Underdog Fantasy, you draft more than one QB. So already you can begin to differentiate yourself with a different second or third QB. And the resulting secondary or tertiary stacking options that follow.

The other bigger difference is who you are competing against. In DFS, everyone competes against everyone on Sunday, so your lineup will go against 100,000 other lineups immediately. In a best ball tournament, you aren’t directly competing against all the other entrants right away.

Here’s the 2021 format for Best Ball Mania II:

First 14 weeks (round one): The top two teams from each 12-person division advance to round two.

Week 15 (round two): Advancing teams are randomly put into 18-person pods. The top two from each pod advance to round three.

Week 16 (round three): Same structure as round two, but only one team from each 18-person pod advances.

Week 17 (round four): The final 160 people all compete head-to-head to determine the winner.

Yes, there will be other teams who drafted Mahomes-Travis Kelce, just like you probably have on at least one team. However, you are competing against ZERO Mahomes-Kelce lineups in round one. Then, in round two you might face one or two Mahomes-Kelce lineups in your 18-person pod. In round three you may face one or two Mahomes-Kelce lineups again. At no point are you facing off against 10,000 Mahomes-Kelce lineups simultaneously like you are in a 100,000-person DFS contest.