Even the best lessons will serve you poorly if applied to the wrong situation. Large field tournaments in Daily Fantasy Sports (DFS) offer plenty of concepts to incorporate into your best ball entries. But it is not a perfect transition.

In Part I of this series, we covered the ways in which tournaments in both formats are similar. They require optimizing your lineups for low probability outcomes. In both, you should maximize correlation to limit the amount of outcomes you need to accurately predict. You can catch that piece here:

Today we move to the other side. We examine the ways in which you need to shift your mindset coming into a best ball tournament. Finally, we will discuss the key takeaway from this series, and how that manifests differently in each format.

Structural Differences

There are four stark differences between DFS and best ball tournaments that alter the strategy for optimizing your lineup:

-

1) The play period is extended over an entire season rather one slate.

-

2) Only a portion of your roster contributes to your score each week.

-

3) You have to make irreversible decisions on portions of your lineup without knowledge of the rest of your lineup.

-

4) The tournament plays out in multiple stages rather than all at once.

Over the rest of this article, I will draw on those differences to establish ways in which the way you implement the strategic concepts from DFS (from Part I) shift.

Unlearn: Optimizing at the Micro Level

In DFS, there are an array of high-level strategies at your employ. But the money goes to the highest scoring roster each week. In best ball, a 14-week regular season and four stage structure devalue the micro elements of your team.

My first ever article was entitled ‘Optimizing your Dynasty Roster with the Pareto Principle.’ The Pareto Principle states that 20-percent of inputs will account for 80-percent of outputs in any given environment. In other words: don’t sweat the small stuff.

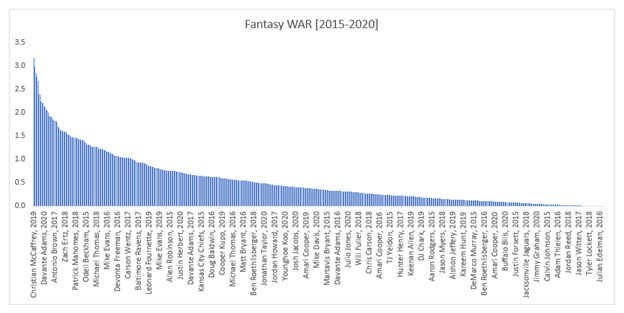

Applying similar theory to seasonal fantasy, Scott Barrett‘s Upside Wins Championships discusses how fantasy football follows a ‘power-law distribution.’ In plain language, elite players account for a grossly disproportionate share of win equity.

Chart Sourced From Fantasy Points

If you had Christian McCaffrey in a 2019 redraft league, you had a 48-percent chance to finish top two. Lamar Jackson‘s rate was 41-percent. Last year, there was no more profitable stack than Josh Allen and Stefon Diggs. Thee advancement rate of such teams was 42-percent; a 250-percent equity increase. The marginal benefit received from useable weeks drafted in the later rounds pales in comparison to the season-altering impact of such a stack or player.

This is a major shift from DFS tournaments where you are competing against the entire field at once, requiring not only the best stack of the week, but the highest scoring pieces around them to win first place. That is not necessary in the first 14 weeks of your best ball tournament, but the macro strategy holds true come playoffs.

A Reversal of Fortune

The power-law distribution has unique ramifications for best ball tournaments compared to DFS or standard best ball leagues. In standard leagues, you exclusively compete against teams who don’t roster your players. In DFS, each of your competitors has the opportunity to roster any player. Best Ball tournaments are a mix of both.

If you hit on 2021’s league winner, you have a massive edge in your opening pool. However, it’s assured that player will be the highest rostered among your competition come Weeks 15-17. Thus, the player most likely to bring you to the playoffs has the least marginal impact on delivering you a title with a big playoff performance. The best way to take advantage of this to recall a lesson from part I: assuming you’re right. Each time you make a selection, build the rest of your team as if you’ve just picked the league winner. Ultimately, the best constructed team around the best player is the team most likely to win.

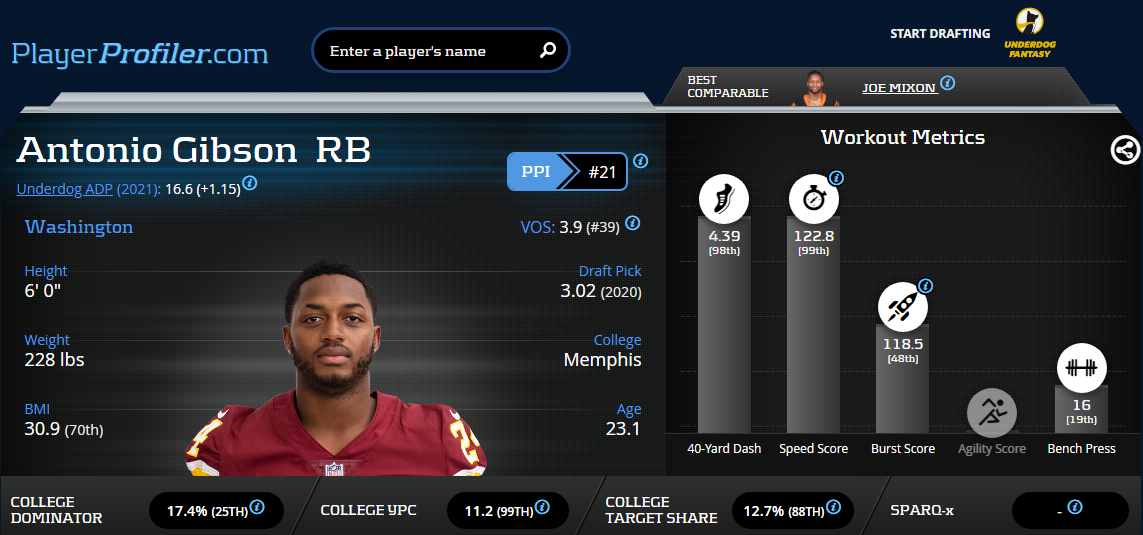

Example: Antonio Gibson is CMC 2.0

You draft Antonio Gibson in round two. You now have two teams you are competing against: teams without Gibson (for 14 weeks), followed by teams with him (for three weeks).

If Gibson cannot perform on par with early round one running backs, he will struggle to post a high win rate for you. But that’s ok because you are drafting under the assumption you are right. Gibson is a top five running back; so treat him like one! Draft the rest of the team under the assumption RB1 is filled nearly every week, and optimize the rest of your roster around him. This strategy is best applied to a player such as Gibson with elite athleticism, pass catching ability and youth.

If he’s the superstar you need him to be, the playoff rounds will be chalk-a-block with Gibson teams. While the Washington star got you this far, your win equity now relies on your ability to build the highest ceiling team around him across three individual weeks. This attitude is especially true with early running backs since we know stud rushers are more stable week to week than receivers, but more volatile season long. The rest of your Gibson-super team needs to be filled with stud wide receivers to fill three (often four) spots, pieces which correlate to Gibson’s success, and a stable of running backs from which one will hopefully emerge as a high-upside RB2.

PlayerProfiler Analytics intern Michael O’Connor wrote of one draft strategy to maximize this outlook: Hero RB.

One reason I’ve been hesitant to take running backs in the back-half of round one is the existence of elite-upside options such as Gibson, Aaron Jones, and Joe Mixon in the second. If the ceiling hits on these players, their points will be be most efficiently used as your RB1, not your RB2. Because you cannot foresee the remainder of your draft at each pick, I prefer to remain as flexible as possible throughout the early rounds.

That being said, I will take it further than ‘Hero RB.’ Competing against teams without a league winner for 14 weeks is a massive edge. But it is followed by three weeks of quasi-DFS where everyone is locked into highest owned player on the slate.

In order to win, you need to expand even further to the tails of your range of outcomes.

If Gibson is the battering ram who brings you to the championship, the RB2 who will complement him against other Gibson teams should be more important than who can give you a useable week against teams who don’t. The best part is, you probably can’t predict who will give you those useable weeks anyhow, as dictated in this thread by Erik Beimfohr. You may as well shoot for ceiling.

Obviously the RB vs WR bit is very fun

But I do think people don't totally understand just how many great weeks come from totally unexpected RBs

Because we can't project it or don't expect it, we dismiss it when drafting even though we know how insane the benefits of it can be

— Erik Beimfohr 🙌 (@erikbeimfohr) July 19, 2021

This is an isolated hypothetical to which you could list off hundreds of ‘what about if ___ happens’ retorts. But that is the point. We are playing 17-week Plinko when it comes to the range of outcomes in a given fantasy season. Applying a macro strategy of ceiling optimization will set you up to maximize your win equity on the rosters your players hit how you need them to.

One such bet has already paid off in deeply unfortunate fashion. Read my latest piece on Darrell Henderson, and takeaways from this example for ceiling-based drafting in tournaments.

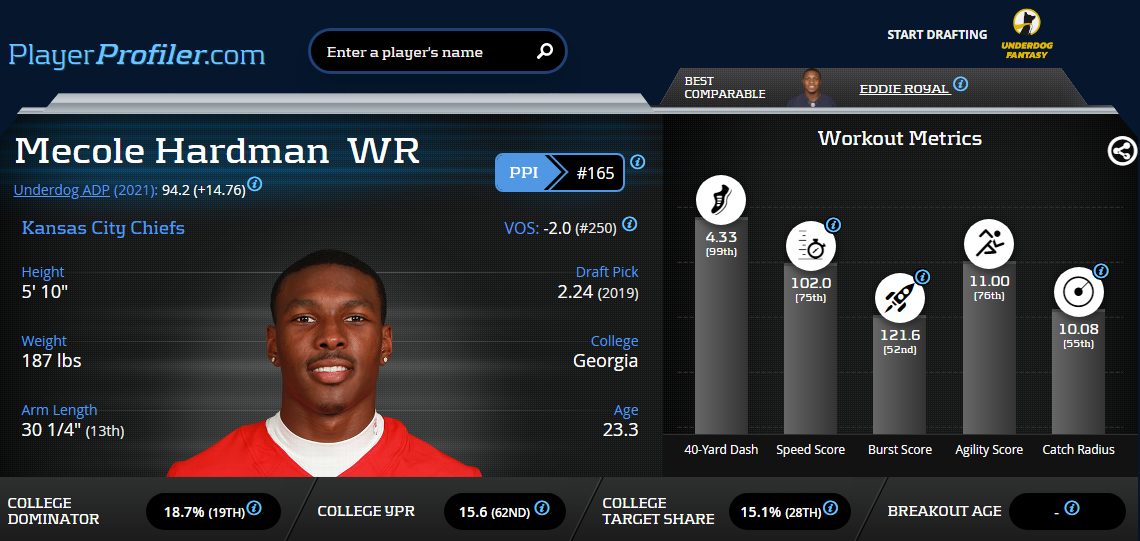

Unlearn: Mecole Hardman is Better in Best Ball™

A difference between best ball and DFS tournaments we’ve yet to explore is the length of the play period. This affects how you analyze variance.

In DFS, you maximize volatility within a single game to increase your ceiling. Between two players with similar weekly medians you will always opt for a Mecole Hardman over a Hunter Renfrow. This has been accepted as a perfect translation to best ball and I don’t understand why.

Occam’s razor states the hypothesis which requires the smallest number of assumptions is most likely to be correct.

Whatever weekly edge is gained by amassing an army of high volatility players, it is far from the simplest path to league-winning upside. Consider the ambassador of the Better in Best Ball™ movement:

Despite his big play reputation, there is no basis for Hardman’s season long ceiling. Hardman, whose College Dominator Rating was a pitiful 18.7-percent (19th-percentile among qualified wide receivers) has not attracted more than 10-percent of targets in an NFL campaign, and is at-best the third receiving option in Kansas City.

While this can be excused in a single DFS week, over a full season Hardman (ADP: 94.2) carries nowhere near the upside of Corey Davis (ADP: 108.2), Elijah Moore (ADP: 108.2) or Marvin Jones (ADP: 115.4). Each of these three have a history of high-volume receiving work in college and/or the NFL, and reside on ambiguous depth charts. Rather than attempting to string together an array of spike weeks from tertiary options, Lord William of Ockham and I will target players who have the best chance to elevate their standing from mid-round flier to every-week fixture.

The top end of the power-law distribution referenced earlier is amassed by season long studs at great value, not isolated long touchdowns.

Unlearn: Forced Uniqueness

In tournament DFS, your goal is to ‘flop the nuts;’ i.e. create the best possible lineup. In a tournament on par with the size of Underdog’s (50,000–plus entries), your margin for error is extremely slim. Because of this, it’s worth considering low probability outcomes in an effort to gain small edges at the micro level. This is often done by exerting leverage. In DFS, leverage relates to making a bet against a given player who projects well and will be highly-rostered, hoping to gain a disproportionate advantage from your bet being correct.

This harkens back to the idea of expected value from the first article. Again, let’s use a real life example:

You are at a 100-person raffle draw with two stages. First, the emcee spins a wheel to determine which bag the winner will be drawn from. Then they pick a name from the winning bag.

Two thirds of the spots on the wheel are reserved for bag A. Only one third is for bag B. Because of this, 90 of the attendees place their ticket in bag A. If you are one of the ten in bag B, your odds to win are actually better (1 in 30 compared to 1 in 135).

In DFS, employing this strategy can be effective. Using an example from Josh Larky‘s recent podcast on stacking: what if you take Michael Thomas instead of Keenan Allen to pair with Allen’s teammate Justin Herbert? If these two were the same price in DFS (as they are a similar ADP in best ball), this could be a prudent use of leverage. Play Herbert with Mike Williams to retain correlation, while leveraging off Allen in hopes Thomas outscores him and you have a highly unique roster.

People applying this to best ball are in the right head space but applying it incorrectly.

Leverage and Median are Linked in Best Ball

The easiest way to create leverage in best ball is by drafting optimally. E-Z game right?

We just discussed how to use the salary cap in DFS to create leverage at a given price-point. The only way to create leverage by altering the salary structure in DFS is by ‘leaving money on the table,’ a strategy the data does not support. Unlike DFS, you can effectively spend over the salary cap in best ball. Because there is no fixed value restriction in a snake draft, the salary cap proxy is ADP. If you draft players who fall, you’re building teams which theoretically should be impossible. In one fell swoop, you make your team better, and more unique. It is akin to scrolling your DFS lineup optimizer, sorting by highest projected, and finding the best plays are also the least owned.

Remember: unlike in DFS, all players in the bulk of the draft will have the same rostership (8.3-percent). Uniqueness comes via combinations of players, not the players themselves. You can either do that in a way which hurts your correlation (the Allen/Thomas example), hurts your expected value (reaching), or improves your expected value (taking fallers).

Unlearn: Get Your Guys!

Have you ever heard the term “play whoever you want” in DFS? It’s often misinterpreted.

Nobody recommends filling out lineups with $1,000 salary left over in the milli-maker because you wanted to ‘get your guys.’ Play whoever you want’ actually means ‘any set of correlated pieces can be viable in a given slate as part of a well-constructed lineup.’

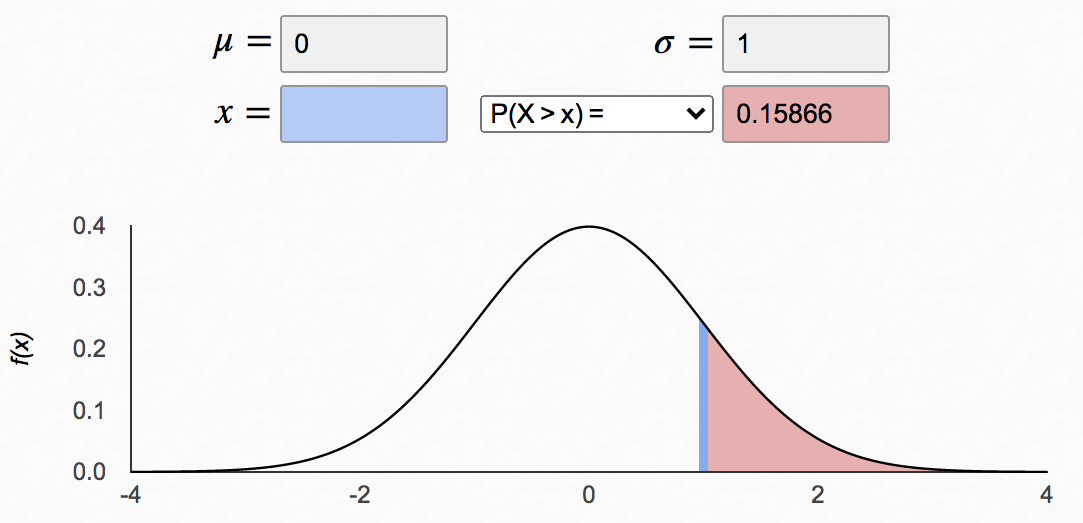

There is a concept in statistics called the ’68-95-99.7′ rule. It states 68-percent of outcomes in a probabilistic sample occur within one standard deviation of the mean in normal distributions. If we assume a player’s draft position is a normal distribution, there is a 32-percent chance an outcome is one standard deviation outside the mean, and a 16-percent chance they fall one standard deviation past ADP (see below chart).

The draft distribution is not perfectly normal, but the theory fits well enough to make use of the concept. Approximately 16-percent of the time any given player will fall materially behind ADP. You can wait on ‘your guys’ until they are at least even with ADP and still gather a decent exposure.

Aristotle once said “the many, though not individually good, when they come together may be better collectively, than those who are so.”

This concept is known as wisdom of the crowds, and it applies best ball. If you are drafting one team and want to take your guys I will not begrudge you. If you’re entering a portfolio of teams you should embrace the wisdom of ADP. You need hit on the right players, and build the best possible teams around those players.

If you take Josh Allen in round four after taking Stefon Diggs in round once, you have a nice stack. It’s possible their correlated ceiling will lead both to pay of that price. But it’s unlikely your team will beat out the Allen-Diggs teams who took Allen round five and accompanied them with a round four player. Josh Larky raised a similar point on Code Breaker.

Set up multiple stacks in advance so you can wait to get yours at the best value. Do the same with your favorite assets.

Takeaway: Leverage your Narrative

You’ve made it to the end of Part II of a complex, longwinded series and for that I appreciate you. I will leave you with one last takeaway to sum up the work of this project.

Each selection you make is a portion of a narrative leading to your million dollar victory. Because of that, you cannot view each pick in isolation. You have to be intentional with each pick as it aligns with the team you’ve constructed to this point: a concept echoed by Neel Gupta on the latest Code Breaker:

Code Breaker Ep.11: @jlarkytweets and his analytics intern @neel2112 discuss the game theory behind intentional drafting, stacking in best ball, and more ⚡

🎧 https://t.co/ouf8CBg5zv pic.twitter.com/hcxce3JfX4

— PlayerProfiler (@rotounderworld) July 25, 2021

For me, this means two things:

-

1) Drafting players whose ceiling output can be most efficiently used in your lineup.

-

2) Drafting players whose ceilings are correlated to the ceilings of players in your lineup.

Both concepts have been discussed throughout both parts of my series and across the RotoUnderworld empire. Being the drafter who takes it to the farthest extreme can grant the largest edge. One of my favourite examples is pairing backup running backs with pass game options in low volume pass games. For instance, if you have a Titans stack headed by Ryan Tannehill, why not add Darrynton Evans in Round 17?

The opportunity cost and payoff on Evans is not materially different than many similarly-priced options, but taking Evans allows you to maximize the benefit of a Derrick Henry injury. Not only would Evans’ expected value increase, but the team would also project more pass-heavy.

As you build your best ball roster, tell yourself a story of how each selection contributes to your win condition. Our ability to predict a league-altering event is quite low. But your ability to set yourself to reap the greatest benefit from any given event is within your control.

The Final Word: Think Outside The Margins: Win Within Them

An analysis of DFS concepts’ applications to best ball will give you an edge at the strategic level. By out-thinking your opponents at the macro level, you will uncover value at the margins that could be the difference between a profitable season and $1 million dollars.