Josh Larky’s recent research on stacking in best ball has hopefully shown doubters once and for all that stacking dramatically increases your chances of winning in leagues and tournaments on Underdog. Correlation between your top players is necessary to reduce the amount of variables you need to get right to go your way.

Josh only discusses best ball within the scope of his article; his data is from last year’s Best Ball Mania tournament on Underdog, and his conclusions are confined to that format. However, his research can be leveraged to talk about redraft leagues everywhere. And it makes a stronger case for stacking in redraft than in best ball.

Seasonal Correlation

Stacking is built on the mathematical concept of correlation, but correlation comes in different forms and is often vaguely identified. Being precise about the type of correlation between players is essential to understanding the difference between stacking in traditional leagues, where you set your lineup intentionally, and in best ball leagues where your lineup is optimized after the fact for you.

The primary form of correlation that benefits fantasy football gamers everywhere is season-long correlation.

If Keenan Allen has a good year and beats his ADP, then Justin Herbert probably will as well. If Tyler Lockett has a monster year, Russell Wilson was most likely allowed to cook, and D.K. Metcalf will also reap the benefits. In fantasy football, players’ ranges of outcomes are correlated over the course of the season. Players don’t operate in a bubble; the NFL is a complex and dynamic system where players’ successes and failures affect each other.

Season-long correlation is the primary force behind why stacking is a necessary strategy in all fantasy formats. When you take Allen in the third round of your fantasy draft, the success of your team hinges on him outperforming his draft position. In order to win your fantasy league, you probably need your quarterback to outperform his draft position as well. Instead of taking Jalen Hurts and praying that both he and Allen outperform their draft positions entirely independently of each other, you should take Herbert, because his season-long outcome is correlated with Allen’s. Now, your win condition does not depend on both the Chargers offense and the Eagles offenses beating expectations, but only the former. The probability of your team hitting its ceiling has increased.

Season-long correlation benefits gamers in both best ball and traditional leagues. Whether you’re setting your lineup or not is entirely irrelevant to wanting your top players’ probabilities of outperforming their expectations to be correlated. You want your team to score the most points in both formats. By drafting a set of players whose individual outcomes are dependent on as few variables as possible, you are increasing your probability that all of them hit.

Weekly Correlation

The other type of correlation is week-to-week. Justin Herbert and Keenan Allen have week-to-week correlation. Let’s say Herbert throws four touchdowns in week six. There’s a solid chance Allen caught at least one of them. Herbert’s success is an indicator of Allen’s success on a weekly basis.

However, with the Seahawks wide receivers, D.K. Metcalf and Tyler Lockett, when one player catches a touchdown, it directly reduces the amount of available points to the other player. Let’s say in Week 7 against the Arizona Cardinals, Lockett scores 50 PPR points and goes for 200 yards and three touchdowns. Metcalf might just go for two catches, twenty three yards, and four PPR points (yes, this happened). While Metcalf and Lockett both beat their ADPs last year because the Seahawks passing offense as a whole beat fantasy gamers’ expectations, on a week-to-week basis, the success of one player often meant a slow day for the other. Metcalf and Lockett had much stronger seasonal correlation than week-to-week correlation.

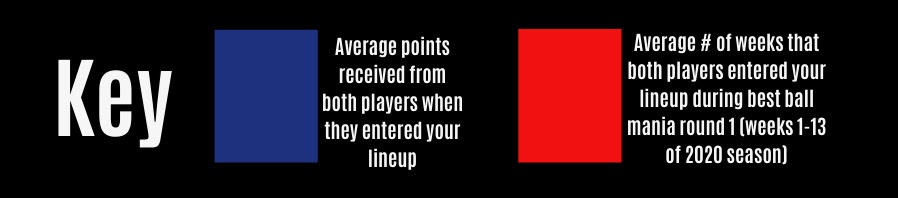

Josh breaks down the week-to-week correlation between quarterbacks and wide receivers in the following table based on Best Ball Mania tournament data from 2020.

From Josh’s article:

“The way to interpret this table is as follows: the red number top right is the average number of times that the QB-WR duo entered peoples’ best ball lineups from weeks one through 13 of the 2020 NFL season (round one of this tournament was cumulative points from the first 13 weeks of the season), and the blue number in each box is the average fantasy points scored by both players during the weeks that both entered your lineup. All these QB-WR combinations appeared in at least 100 different teams in the tournament to ensure adequate sample sizes were reached.

As an example, among teams that drafted both Patrick Mahomes and Tyreek Hill, both players entered best ball lineups in 9.1 of the 13 weeks on average, scoring 50.2 combined fantasy points when they did. On the other hand, teams that drafted both Mahomes and DeAndre Hopkins had that pair enter their best ball lineups together only 6.7 of the 13 weeks on average, for only 42.2 fantasy points combined per week.”

Almost every top QB-WR pair on the same team had more weeks when they entered your lineup together and averaged more points than pairs of top quarterbacks and wide receivers that aren’t on the same team. Josh is using week-to-week correlation as an argument for stacking in best ball.

We, Michael and Neel, the summer analytics interns, disagree with Josh’s interpretation. While this table is incredibly compelling, it tells us more about the importance of stacking in traditional leagues than it does for best ball.

Why Stacking is Stronger in Redraft than Best Ball

Best ball leagues optimize your lineup automatically after the week, and reward you at the end of the season if you had the most points scored overall. Unlike traditional leagues, where wins and losses are the most important metric to determine whether you make the playoffs, the best ball format removes the variable of a weekly opponent and instead focuses solely on the points scored metric.

In best ball, the amount of points a player contributes to your lineup is purely dependent on their own performances and the other players at the same position on your team. Tyler Lockett will enter your lineup on average for a certain portion of the season, Russell Wilson will enter your lineup on average for a certain portion of the season, and Patrick Mahomes will enter your lineup on average for a certain portion of the season. As Josh’s research shows, Lockett and Wilson did enter your lineup as a pair more often than the pair of Lockett and Mahomes. That’s just how week-to-week correlation works. But all that means is the portion of the season where Lockett entered your lineup lined up with the portion of the season Wilson entered.

In other words, stacking’s week-to-week correlation alters when your points come over the course of the season, but does not alter how many of them you score. The pair of Mahomes and Lockett would have produced more points towards your best ball roster than Wilson and Lockett, those points would have just come in different weeks.

In traditional formats however, we care more about weekly spike weeks. We care about the when. A gamer that starts Mahomes and Lockett each and every week actually makes more incorrect decisions in setting their lineup than the gamer that starts Wilson and Lockett each week. Our table tells us that in the first 12 weeks of the season, Wilson and Lockett as a pair were on average the best option in your lineup about seven times, and scored an average of 46.8 points during those weeks. Conversely, Mahomes and Lockett as a pair were only the best option in your lineup about six times, and averaged only 44.3 points over those six weeks. All this means is Mahomes’ big weeks didn’t line up as well with Lockett’s compared to Wilson’s. While we outlined above why this doesn’t matter in best ball, it has huge implications in redraft.

You want your players’ spike weeks to line up in traditional leagues to ensure that you win those weeks. If Mahomes’ and Lockett’s spike weeks are not aligned, then you might waste a good week by one of your studs because the rest of your team let them down. Week-to-week correlation in traditional leagues ensures that your team converts good weeks from your players into wins. Wilson and Lockett’s seven weeks where they entered your lineup in best ball corresponds to seven likely wins for gamer that started those players each week in traditional leagues. On the other hand, Mahomes and Lockett were only the best option as a pair six times when you started them, and your weekly payoff was lower each time, leading to a lower expected win total over those weeks.

Visualizing Spike Weeks

This graph allows you to visualize the spike weeks exhibited by some of the top stacks mentioned in Josh’s article.

Here, you can select (really, click on the quarterback names on the right to select/deselect which ones are graphed) the quarterbacks you want to pair with each wide receiver: the weekly point totals for all 30 combinations from Josh’s article are shown. From this graph, we can easily see the significance of week-to-week correlation as we’ve just shared.

Josh’s article lays out empirically that stacking in general increases your win rate in Best Ball and is one of the most necessary tactics to learn in order to make money on Underdog over a large sample size. We posit that the strength of stacking in best ball formats stem almost entirely from season-long correlation rather than week-to-week correlation.

On the other hand, by stacking in traditional leagues, you benefit from both season-long correlation and week-to-week correlation.

By implication, we expect stacking in traditional leagues to have a larger increase in your win probability than in best ball leagues.

Here, we’ve compared the average non-stack for each week to each of the six stacks from Josh’s first table. The theory we’ve operated under is that stacking players for their week-to-week correlation will increase your weekly win probability. But did you end up actually winning? To account for the uncertainty of every possible non-stack combination (you can’t always have the best non-stack), we’ve compared each of the six stacks from Josh’s article to the average non-stack and have displayed the difference in point totals. Essentially, any point above the dashed line (positive difference) is a stack that performed better than the average non-stack for that week.

Five out of the six stacks finished above the average non-stack more often than not. That means that five out of the six stacks are giving you a winning record at the QB-WR position pair even against some of the pre-selected for high-scoring QB-WR pairs that we’ve studied here.

Obviously, not every stack will work out as expected: Watson & Cooks vs. Watson & Hill seems almost unfair; however, it’s clear that the week-to-week correlation you gain from stacking provides you with a unique advantage over the rest of the competition. But is that advantage worth reaching for?

Final Thoughts

Given all of the advantages stacking provides you with, we are more willing to reach for a stack in leagues where you have to set your lineup and accumulate weekly wins than we are in a best ball format. Reaching for a stack actually decreases the chance your players outperform their draft position over the course of the season regardless of the season-long correlation. In traditional leagues, even if your reach negates some of the benefits of season-long correlation, you still have bankable week-to-week correlation to ensure that your players’ spike weeks line up, and you get yourself some wins.

We’ll leave you with a few of RotoUnderworld’s approved stacks for your redraft teams. Using current ADP data, here are the best stacks from each draft slot. Note that these may change based on how your draft plays out:

1.01 – Justin Herbert & Keenan Allen

1.02 – Ryan Tannehill & A.J. Brown

1.03 – Dak Prescott & CeeDee Lamb

1.04 – Joe Burrow & Ja’Marr Chase

1.05 – Russell Wilson & D.K. Metcalf

1.06 – Matthew Stafford & Cooper Kupp

1.07 – Lamar Jackson & Mark Andrews

1.08 – Patrick Mahomes & Tyreek Hill

1.09 – Kyler Murray & DeAndre Hopkins

1.10 – Josh Allen & Stefon Diggs

1.11 – Aaron Rodgers & Davante Adams

1.12 – Tom Brady & Mike Evans